Recently in a class I was asked the usual question: how long should I do rope before I try suspension?

Before I tell you how I answered it, I’d like you to ask yourself one question: in your mind, who did you picture asking the question – a top or a bottom? Whatever you answer isn’t necessarily relevant to the risk management stuff that follows, but it’s an interesting insight into your view of who invests in and needs rope bondage education.

I gave Sex Education Standard Answer No. 2, “It depends” (No. 1 is, of course, “communication”). I pointed out that you could learn a single column tie and a taut-line hitch and where to put them on your partner in about 45 minutes and do a suspension; however, you could spend years of training and not be able to do some of the wild-n-crazy stuff that people like m0co and Beemo do. All suspensions are not created equal.

After the class I was approached by a colleague – and that’s being egotistical, as she’s actually a much more skilled rope enthusiast than I was. She disagreed with my assessment of time. “Yes, you could learn the basics of a suspension,” she pointed out, “but you wouldn’t have the experience to deal with everything that could go wrong!”

I went for the easy target of hyperbole: “Anyone who thinks they have the experience to deal with everything that could go wrong is a walking manifestation of the Dunning-Kruger effect,” I said. She looked annoyed (and rightfully so; that was a cheap shot on my part) and modified her statement to “…the great number of things that could go wrong.”

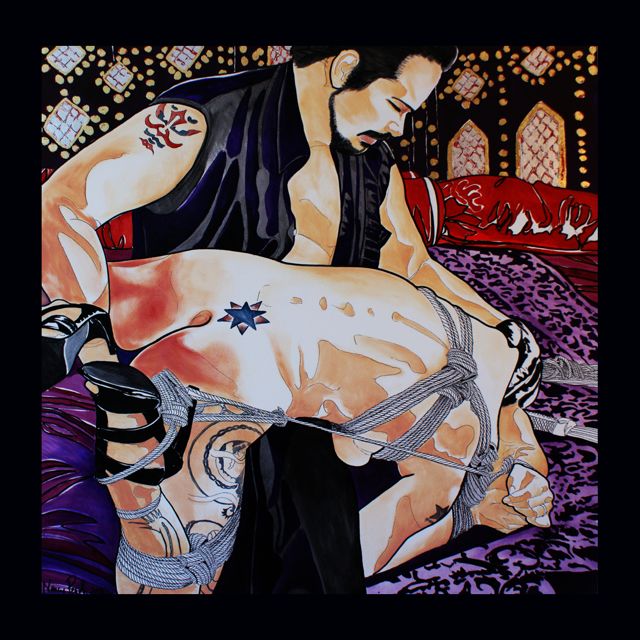

Which is a very valid point. My statement about the 45-minute suspension is based on an experience I had in the Marine Corps. It looked something like this; I’d especially like you to watch from the :34 – 1:26 mark:

First, notice the number of people that are about to be suspended. Remember, also, that these are not Marines; these are Marine recruits, and while I love the Corps, I can tell you from personal  experience these are not examples of the most skilled learners. All of these people are being taught how to tie a very basic swiss seat (see left) and then taught how to attach the line to a carabiner and rappel down the side of a building.

experience these are not examples of the most skilled learners. All of these people are being taught how to tie a very basic swiss seat (see left) and then taught how to attach the line to a carabiner and rappel down the side of a building.

How many of these recruits fall to their death? I did a search, and couldn’t find statistics that were reliable. However, there is a relatively high injury rate in general for recruits (17%) and of those the vast majority were related to running (shin splints, etc). What I can tell you is that no one was injured during my experience, and a quick web search for “Marine recruit injured rappel” pulled up no significant results in the first few pages (except this one, but that’s the Army, so totally irrelevant). How is this possible? Considering that we talk about people taking “years” before they should even look at a carabiner, how does the most elite fighting force ever known* manage to keep recruits from plummeting to their death?

Recruits learn how to make their safety harnesses, or seat, using six feet of rope. They wrap the rope around their legs and hips, securing it with a series of square knots. “Safety is very important during this phase of training,” said Sgt. Mauricio Ramirez, drill instructor, Instructional Training Company. “We check the recruits’ safety harnesses three times before they rappel.”

Get that? Not twice. Not four times. Three times. Because as they line up for the tower, there are checkpoints where the instructors make sure the DARs (DumbAss Recruits) have actually tied it correctly. And tight enough. And while I don’t know what they were exactly, I’m betting that the Drill Instructors had a very specific list of points to check on each recruit. It’s similar to the way the DI was teaching how to rappel, breaking things down into easily-repeatable mnemonics. I do the same thing in my “Tie Em Up & Fuck Em” class: Secure the hands. Wrap the body. Control the hips.

By creating a system, they control the variables. The recruits have a standard length of rope, a standard carabiner, a standard way of tying the rope. That’s how you can learn suspension in 45 minutes: a single column tie, a taut-line hitch, a face-up suspension done low enough to remove a great deal of the risk of falling (certainly to below the risk of tripping on the mat, say).

Incidentally, you know what the official term is for a suspension that holds someone 4″ off the floor?

It’s called a “suspension.” Also, I know of no cases of wrist drop/strangulation/leprosy/meninitis or any other significant injury from a single-column tie around the hips or around the chest. Ligature marks, maybe. Shortness of breath, hardness of cock, wetness of cunt, sure, those are common, but easily dealt with using a variety of remedies. This is why I stand by my assessment of 45 minutes (or less) is all you need for a basic suspension. The risk factors are mitigated by that one word: basic.

The real risk, to my mind, is boredom. It takes true skill to make a basic suspension exciting, connective, and/or sexy. And that’s for tops, bottoms, or anyone else.

I’d like to suggest that we stop giving arbitrary answers like “in-person training” or “four years” or “have you bought my DVD?” to the question of When can I suspend? Instead, it should be answered much in the same way the phrase sexual contact is: What does that look like to you? If the answer is “I want to be the next Murphy Blue!” then that’s going to be different than “I just want to feel like I’m off the floor.” Let’s talk about actual risk, and quit falling into the lazy trap of pretending that it’s all OMG GOING TO KILL YOU.

All suspension risk is not created equal.

Tell me why I’m wrong! Also, part 2 will deal with suggestions straight from Risk Management science to more safely do the non-basic stuff.

- * Admittedly, I may be biased. #OORAH

Follow

Follow

Yay! I must share

I agree that a bunch of single columns have reduced risk, and the basics can be taught to a committed and attentive student in a very short period of time.this isn’t risk free, but it’s certainly not the minefield that some really skilled riggers manage to navigate.

I also appreciate your opening question about how we have certain assumptions about who needs to spend how much time before engaging in suspension. the really incredible suspensions come from teamwork and it takes an incredible amount of skill and training to pull those off.